I’m sure this exists in some Umberto Eco book or something somewhere-

But imagine a man who is supernaturally bestowed with the power to truthfully answer any question someone else poses to him, but only on the terms that the question was posed. Our poor supergenius, call him Bert, cannot add new vocabulary that the asker doesn’t already use. He can’t draw or move to better convey his answers to others’ questions visually. Poorly posed questions about elan vital or phlogiston or angels on pinheads get warped answers, instead of denials of the premises (perhaps because if Bert had to deny all false or vague premises, he’d never be able to answer anyone’s questions at all). Even well-designed questions with direct answers might suffer from an “Up-Goer Five” effect, where Bert has to constrain the absolute truth to terms and ideas that already exist, leaving him frequently tongue-tied or unintelligible. There are clean-cut and simple answers that he cannot give especially well because of his inability to expand vocabulary or introduce new concepts. There are simple questions that he wished someone would ask but if never occurs to anyone to ask in the right way, most of the time. Many of what people bring to him as Big Questions are instead just very confused nonsense that he can only answer with his own tortured nonsense response.

We are not equipped to understand Bert.

Just as there are odors that dogs can smell and we cannot, as well as sounds that dogs can hear and we cannot, so too there are wavelengths of light we cannot see and flavors we cannot taste.

Why, then, given our brains wired the way they are, does the remark “Perhaps there are thoughts we cannot think” surprise you?

Evolution, so far, may possibly have blocked us from being able to think in some directions; there could be unthinkable thoughts.

-Richard Hamming, Bell Labs

An affordance is a possibility for action, latent in the designed artifact itself but recognizable and actionable to the user. Knobs and wheels afford turning. Buttons afford pressing. The possibility for the action is clear just by looking at it- at least, for someone who has already mapped the mechanics of an artifact to an experience they recognize.

One could imagine an alien species with strange appendages and sensory organs, creating tools that seem very natural to them because of their history and what their bodies allow, tools that for humans are worse than unusable- they’re practically unfathomable.

I want to take a stab at thinking about what is and isn’t “fathomable”.

Analogical Reasoning and Banality

I assume most people who ever bother to read this are, in some sense, naturalists. In our everyday lives, things don’t come out of the void. I submit, without dwelling on it much here, that new ideas are either re-combinations of old ideas or the introduction of new data that can be explained by some analogical framework (this thing is like that thing). Eventually new vocabulary can be engineered to explain a thing on its own terms, but that process comes later- for example, mathematical notation was invented to help manipulate symbols that were already understood, but the very existence of mathematical notation allowed people to begin to think differently about algebra (eg. what if x was not a number that we knew about beforehand?). People cannot and do not suddenly find themselves the stewards of supernaturally-acquired information. Brand new ideas are serendipitous connections between information that exists now.

Douglass Hofstadter used the concept of “mother” to explain the strength of analogical reasoning. A sensory experience of a thing labelled “mother” comes first- mother is what feeds me. The schema for mother evolves as more information and better reasoning become available. Other children are like me, and they have mothers like I have a mother. Grown-ups come from children and so grown-ups have mothers, too. Animals have mothers. Mothers have mothers. There is an idea of “being a mother” or “mothering” in the abstract. The French Revolution was the mother of the Haitian Revolution.

I imagine that our expanding empathetic circle is also primarily understood as the logic of analogy. Civic duty is analogical to familial duty. Our idea about who our neighbors are (i.e. who deserves our consideration) is constantly shifting.

We casually skip middle-steps in this analogy game as adept language/logic manipulators (ex. To “bork” something, to “undress a banana”). But, ultimately, everything you can know and explain must have grounding in a concept or in a sensation that you share with whoever you’re explaining to.

Analogy, I think, is also the key to normalizing processes that we might otherwise find radical. In recent decades, massive technological revolutions have occurred and didn’t leave us reeling because all of the weirdness is humming in the background- interfacing with humans properly is an exercise in carefully constructing familiarity, in making people feel comfortable by offering affordances and skeuomorphs and experiences that are understandable and providing feedforward about what is doable and what to expect. I remember reading about early “conversational” computers having to arbitrarily pause before they responded to human inquiry because immediate responses felt unnatural. When I imagine future technology, I don’t imagine the people in them feeling as confused as I would be, because they are not me. They’ve been guided along, the same way we’ve been guided along from the era where black-and-white shorts of a train coming at the screen would frighten and delight movie audiences. I imagine that, once commercially available, even the most extreme technologies will be seen as banal, rolling up slowly over the trough of disillusionment.

The most interesting, comprehensive view of this concept comes from one of my frequent sources, Ribbonfarm.

My new explanation is this: we live in a continuous state of manufactured normalcy. There are mechanisms that operate — a mix of natural, emergent and designed — that work to prevent us from realizing that the future is actually happening as we speak. To really understand the world and how it is evolving, you need to break through this manufactured normalcy field. Unfortunately, that leads, as we will see, to a kind of existential nausea.

(A good summary of the Manufactured Normalcy Field by another party is available here.)

Alien technology may not necessarily be a problem of determining function, especially if they are like us in enough ways to get the gist of what functions are likely- it’d more likely be a problem of interface/analogy. Their separate technology tree doesn’t feed on our history and our understanding, it may not be easily understandable as an analogy to something that we are familiar with, and depending on how different they and their environment are (Are they cephalized? Bipedal? Carnivorous?) the design space might not even find them making similar technologies based on “forced moves”/”good tricks“. Their technology may not afford very much to us at all. It might just seem like magic.

Established ideas become obvious and boring at the appreciative level. What we can talk and think about analogously to what we have already explicitly conceived and perceived, I think, is the edge of imagination.

Rhetorical Affordances

In a research paper shared with me recently I was introduced to Rhetorical Affordances, a concept that combined this design-talk of affordances with the media studies-talk of procedural rhetoric that I aired a few weeks ago. Like a functional affordance, a rhetorical affordance is latent in the designed artifact but must be recognized by a user who understands similar scenarios. A rhetorical affordance affords a narrative.

Rhetorical affordances are the opportunities for representation made available by the rules that govern the relationship between objects and processes in a system. The meaning that is being selected from a set of possible meanings afforded by a game mechanic is a product of its relationship with other dynamics in the system and the interpreter’s beliefs about the instantial assets that specify its domain.

–The Micro-Rhetorics of Game-O-Matic, 2012 (Treanor et al.)

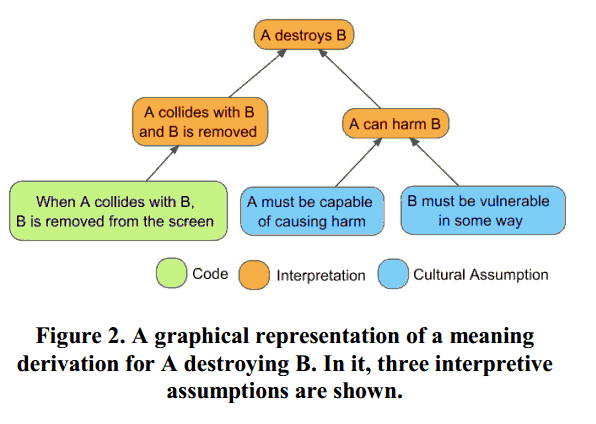

Below is a chart lifted from the same paper.

You could easily imagine other mechanics, mechanics devoid of any explicit graphics, and how easily stories can be constructed from simple dynamics. Imagine interactions between three kinds of circles, (A, B, and C) and being able to set or check even a few variables: checking for collision with each other, changing scale/size, direction, speed, color, and checking/creating/removing instances of A, B, or C. Imagine how easily you could create a game of tag, or a pong match, or a shooting game, or Snake or Pacman. The mechanics/interactions afford a story or scenario.

People have a long history of assuming agency in non-human things and analogizing nonhuman events to understandable human ones. Even in naming and numbering things, scenarios about norms and movements and intentions are born.

Weird Fiction and the Unthinkable

So what happens when the stories don’t clearly map to an experience, and analogical reasoning fails?

Parker slipped as the other three were plunging frenziedly over endless vistas of green-crusted rock to the boat, and Johansen swears he was swallowed up by an angle of masonry which shouldn’t have been there; an angle which was acute, but behaved as if it were obtuse. So only Briden and Johansen reached the boat, and pulled desperately for the Alert as the mountainous monstrosity flopped down the slimy stones and hesitated, floundering at the edge of the water.

-The Call of Cthulu

The pleasurable thing about Weird Fiction is that it does not presume that you, the reader, deserve to know (or are even capable of knowing) the mechanics of the world. Cthulu is described as a vague, contradictory amalgam of at least three very different animal forms, and much more. Angles with contradictory properties (acute and obtuse?) behave (behave?!) in a way that suggests that the inherent mathematical nature of the angle leads it to “swallow up” people. And no more is offered to you. In magical realism, the magic is established as a property of the alternate history, usually one that characters understand or cope with in some sense. In Weird Tales, however, humans are weak characters and unreliable narrators in a Cosmicist universe, unable to perceive or understand greater forces at work- not benign, angelic forces or evil, demonic forces, but something somehow worse: indifferent forces who don’t know or don’t care about human intention. Forces older and perhaps more intelligent and certainly utterly inscrutable. There is no promise of future understanding. There is no established logic to hold onto.

The human race will disappear. Other races will appear and disappear in turn. The sky will become icy and void, pierced by the feeble light of half-dead stars. Which will also disappear. Everything will disappear. And what human beings do is just as free of sense as the free motion of elementary particles. Good, evil, morality, feelings? Pure ‘Victorian fictions’.

-H.P. Lovecraft

I was reintroduced to the Weird through House of Leaves, maybe five years ago. My favorite book of the sort is Ligotti’s The Conspiracy Against the Human Race, (which is a nonfiction, weirdly). I enjoy Weird Tales as a sort of counterbalance to the progressiveness and rationalism of proper science fiction (which I also enjoy). Science fiction tends to be secular, humanistic, and fundamentally understandable, even while engaging the same sort of open speculation as Weird Fiction. Science fiction generally emphasizes the capabilities (constructive or otherwise) of humans and their power to normalize aspects of nature that we can’t yet normalize in our apparent march of progress towards some utopia/singularity or dystopia/apocalypse. Weird fiction denies the importance of humans and the possibility of a fundamentally understandable universe.

I don’t mean to argue whether the truly incomprehensible Weird actually exists, but unthinkable concepts certainly must. I would use Weird to instead mean something we are not equipped to understand, for cognitive or perceptive reasons.

Bret Victor‘s most compelling argument, throughout his corpus, is that by building new tools to view and manipulate, we augment our own understanding of things we can only partially fathom before we really see them. By converting sounds we can’t hear into visual waveforms, or creating new notations and representations (which he analogizes as “user interfaces”), we can expand the set of thinkable thoughts. If we think analogically, nothing that is un-associated with experiences or scenarios we’re familiar with can be known unless we can transform them into experiences we’re familiar with. Being able to create symbols or manipulate forms that represent something that itself is not naturally perceivable gives us control over it almost as though it is naturally perceivable. New representations allow for new affordances to become apparent, changing the way we interact to the same “thing”.

In some sense, Victor imagines that if we find the right tools then we can normalize at least some of the unthinkable and the difficult-to-think-about, by bridging more analogical gaps that allow for humans to assert control: visualize and categorize and manipulate. And once the proper interfaces are in place, even the unthinkable can become banal enough to come to us in shiny, familiar app form- the truly weird and slimy and nonhuman can continue to hum in the background.

Affordance: Attribute of an artifact that allows users to preempt their likely use-case

Functional Affordance: Possibility for action latent in the artifact and identifiable by the user

Rhetorical Affordance: Opportunity for representation latent in the artifact and identifiable by the user

Manufactured Normalcy: Interface of ever-presentness, protecting users from the weirdness of modern technology

Analogical Reasoning: Abductive reasoning, reasoning by analogy. I contend it to be the furthest-reaching method of reasoning.

Science Fiction: Imaginative, future-focused genre of speculative fiction. Secular, humanistic, tends to be fundamentally understandable

Weird Fiction: Imaginative, Cosmicist-focused genre of speculative fiction. Not humanistic, deals with contradiction and brushes with the barely-thinkable/”unthinkable”

Banal: The common, predictable, understandable

Weird: The uncommon, unpredictable, not understood. (In Weird Fiction, the “unthinkable”)

Unthinkable: Concepts that cannot be easily imagined/manipulated, likely because of poor representation or lack of analog to something known and understandable.