Note: I am writing every Tuesday and Thursday now. I noticed much more Thursday traffic than Tuesday traffic this week…

I am currently barely starting A Thousand Years of Nonlinear History (had a turbulent few weeks- my reading time took a serious hit). I’ve encountered attempts at historical accounts at a different perspective than human agency, but never one that has succeeded at going so long, with so much detail, without ever using the vocabulary of human interaction as a crutch. I’m too scared to write about the book yet, I’ll probably wait until I finish at least a part of it.

This post is about the evolution of artificial things over time.

Forced Moves and Good Tricks

I first read Daniel Dennett’s “Darwin’s Dangerous Idea” the same summer I read Herbert Simon’s “Sciences of the Artificial”, maybe six years ago. I generally see those two books as the starting point of my interest that informed my choices of college and majors and prospective career. The vocabulary of cranes and skyhooks and design space and satisficing and bounded rationality are permanently cached away as basic metaphors for understanding how I think about a bizarrely wide array of things. The fact that I haven’t mentioned them, several thousand words into subjects where they would’ve been appropriate, was entirely accidental.

Anyway, I’m starting with Dennett today.

The world of physics is generally described as a world of what can happen, and is meant to be universal. By contrast, biology is more dependent on history, and is therefore more local and exists in the world of what did/does happen as opposed to what could happen. But Dennett also argues that in design space there often exist “forced moves” and “good tricks” that can often be discovered and rediscovered in the right conditions. This is the explanation for convergent evolution, wherein genetically distant species adapt similarly to similar niches across time and space. A “forced move” is an adaptation that is necessary to stay alive in a niche (failure to make a forced move results in extinction). A “good trick” is an adaptation that can be useful in several scenarios that may or may not occur, but would be nice to have if they do (they generally improve resilience). Historical contingency and environment are very powerful drivers in design space:

100 million years ago, when the Earth had its normal hothouse climate and reptiles were the dominant vertebrates, the icthyosaurs, a large and successful family of seagoing reptiles, evolved what we now think of as the basic dolphin look; when they went extinct and a cooling planet gave mammals the edge, seagoing mammals competing for the same ecological niche gave us today’s dolphins and porpoises. Their ancestors, by the way, looked like furry crocodiles, and for good reason; if you’re going to fill a crocodile’s niche, as the protocetaceans did, the pressures that the rest of the biosphere brings to bear on that niche pretty much require you to look and act like a crocodile.

The lesson to be drawn from these examples, and countless others, is that evolution isn’t free to do everything that, in some abstract sense, it could possibly do. Between the limits imposed by the genetics of the organism struggling to adapt, and the even stronger limits imposed by the pressures of the environment within which that struggle is taking place, there are only so many options available, and on a planet that’s had living things evolving on it for two billion years or so, most of those options will have already been tried out at least once. Even when something new emerges, as happens from time to time, that doesn’t mean that all bets are off; it simply means that familiar genetic and environmental constraints are going to apply in slightly different ways. That means that there are plenty of things that theoretically could happen that never will happen, because the constraints pressing on living things don’t have room for them.

Keep in mind that “artificial” is a subset of “natural”, and that is also true in design space.

Waste/Fertilizer

One interest of mine that has shown through on this blog is “how people organize”. I’m interested in how institutions form and why some are generally more successful than others. While these kinds of sociological concerns aren’t an exact science, I tend to think of them the same way I think about other past-sensitive subjects like history and biology. There are generally things that have worked in the past that are likely to work again. There are things that haven’t worked in the past that could work this time, but that is a much riskier bet. I imagine there exist plenty of “good tricks” that can be mined out of history without necessarily knowing how sociological phenomenon work at an irreducible or “global” level.

There is one more vague, you-get-it-or-you-don’t idea I want to air from some of the sources I’ve been returning to over and over in this blog so far, and that’s the idea of older things becoming fertilizer for newer things, subtly changing the environment and allowing for new forms. Even allowing for forced moves/good tricks and the convergent evolution that they appear to make inevitable, historical dependency and environmental pressure are not universal across space and time. Environments are changed by their inhabitants. Organisms consume some things and excrete others, slowly transforming their own world and tuning the environment around them. Stars generate byproducts, too, and when they die they leave behind different stuff than existed before they were alive. Environments change, often in an unpredictable and nonlinear fashion. There may be periods of relative stability before some apparent change occurs suddenly. There is no static natural equilibrium. Older cultures may construct artifacts and ideas and then leave them behind for re-appropriation or re-combination by newer cultures that can salvage what “good tricks” that they discover there, and discard the rest. Living cultures can attempt to steal and copy from each other, as well. Competition is another environmental/historical variable that clearly changes over time, maybe gradually, or maybe in a series of détentes and arms races. The broad point I mean to make before continuing is that just because certain forms may occur and reoccur, they are by no means eternal or inevitable. They are just more likely than other forms that could occur (they are possible) but aren’t particularly likely to (because of the constraints of precedent and environment).

One book in the past year that could be read from this [fertilizer/recombination] point of view is Francis Fukuyama’s The Origins of Political Order, which outlined the development and combination of three elements of political order needed for a successful modern nation-state, presumably written with the goal of diagnosing states that have taken a different path and are failing (by metrics of human prosperity). The three elements he defines are a strong state, rule of law, and political accountability. He attempts to illustrate how historical contingency has allowed different peoples to experience and recombine some or all of the three elements effectively.

Tribes, Institutions, Markets, and Networks

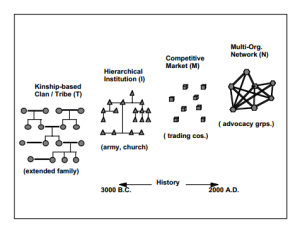

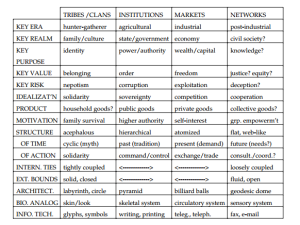

I want to outline one more framework on this topic, called TIMN (Tribes, Institutions, Markets and Networks: A Framework About Societal Evolution).

All four forms co-exist and existed in some capacity for millenia, but the idea is that each successive form has been (or for Networks, will be) better developed and integrated into our political organizations over time. The earliest forms of human organization were almost exclusively tribal, a kin-ship based organization (T). Tribes are extremely resilient, but there are limitations of scale and stability. Agrarian empires of the ancient world used hierarchical structures to organize larger groups of less-related humans (“not common ancestors but a common ruler“) to undergo larger-scale campaigns of conquest and resource allocation in systems we might call “T+I”. Markets existed and were influential but were not grappled with and prioritized as political forms immediately. One limitation of “T+I” organizations is that they can’t “handle complex exchanges and information flows well”, which is especially problematic in the economic sphere. This problem allows for the innovation and maturation of Market organization. “T+I+M” societies arise after the market as a philosophical concept is developed and given a name (and can thus be deliberately manipulated), at the dawn of the Industrial era. Interestingly, other political innovations such as statist communism is treated as a backward development to T+I structures that would never be able to deal with the unique problems that the Market form solves. China’s move towards capitalism is almost seen as a forced move in this view.

Yet, despite all its strengths and contributions to the advance of society, the market system has a key limitation of its own: It contributes to creating social inequities, and does not prove adept at addressing them. As in the case of the earlier forms, the sharpening and the recognition of this limitation takes us to the next form to arise.

And so, the paper argues, the byproducts of the Market form are fertilizer for the maturation of a fourth form, the Collaborative Network, enabled by new communication technologies, new languages and philosophies to describe and measure itself, and resources being poured into innovating it in order to address the limitations of the Market form, in the same way Markets addressed limitations of the Institutional form, in the same way that Institutions addressed the limitations of the Tribal form. Networks are flat, polycentric, and ideologically integrated. So the story goes, the Network is the next step forward (barring, of course, a weakened market and a decay in institutional trust causing some sort of regression to more tribal forms of organization, blah blah.)

There are other interesting details the paper considers that I enjoy.

- Each form further stratifies society. Tribes loved blood- they have “kinsfolk” as the most crucial rank (you either are or are not) with perhaps a fluid sense of rank by other dimensions (maybe age, or centrality to the clan); Institutions love power- they funnel resources across dissimilar peoples through authority, creating a classes of “ruler” and “the ruled”; Markets love capital- they generate comparative senses of wealth as status, often in the form of the tripartite “upper, middle, and lower class”; we can presume that Networks generate some new form based around information access, and can (the paper rashly presumes!) be defined as a four-class system.

- Each form has an unattainable ideal: even tribal societies dealt with markets and hierarchical structures in passing, accidentally. No form is pure. Mature forms have to deal with realities more complex than the abstraction of these forms can deal with. New forms also bear elements from previous forms that can stunt them (clannish relations at the top of institutions, for example).