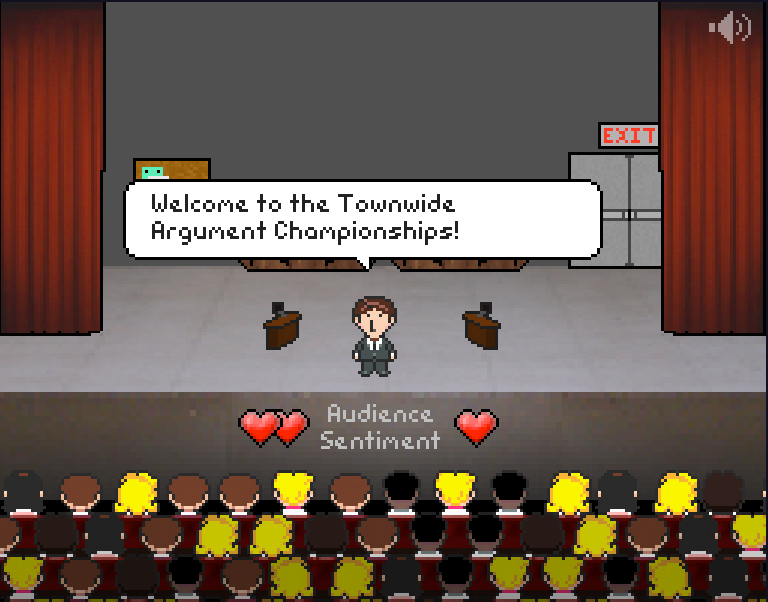

In the game “Argument Champion“, A little demon appears and shows you the thought bubbles of your audience’s beliefs [for example “I like headers” or “I dislike squids”]. Connect “positive” beliefs to your nonsense cause and “negative” ones to your opponent’s, by navigating a grid of related terms and trying to cover the smallest topological distance between terms as possible. It’s that easy!

For example, I was arguing in favor of “Driver”. Someone in the crowd had a positive feeling towards “Headers”, so I clicked on his thought bubble, leading me to a radial tree network where I can only see the neighboring concepts to “Header”. I selected one of the eight-or-so options, “Captain”, and from there I could see that “Driver” was immediately associated. That low distance between concepts is why I’m apparently an excellent debater.

Take a look at the game (it’s in-browser), it’s much easier to just sample than it is to explain in words, though I tried. I was reminded of this game when I started writing the post below.

I.

This came up in discussion recently.

Similar posts: Guerrilla tactics, How To Choke Your Enemies To Death

I took Aikido for a few years as a kid. I’m not supremely confident in my bullet-catching abilities, but it was good for me and I’m glad I did it.

Aikido is about using the opponent’s movement against him, instead of willfully overpowering him. It’s very throw-based, and usually the setup involves identifying and “leading” the opponent’s body and then turning it in a way he finds uncomfortable. To see it done well is viscerally very satisfying.

Sophism is a kind of rhetorical Aikido style. I’ve written before, channeling Huizinga, that the Sophists’ goals were not some higher Truth, but “excellence” (ie. victory in the game of “debate”). I could imagine the Sophist teaching the art in combat terms. What is the enemy’s position? How can we force them somewhere they don’t want to be? How can we turn the audience against them?

Before Plato poisoned the well, “Sophist” could be used as a positive or snide term, like “Intellectual” or “Elite” today. But we all know what sophistry means now- practiced “intellectual dishonesty”: you may not be lying but you are intentionally deceiving. You are likely taking the opponent on bad faith, leading his hand somewhere he didn’t mean so that you can throw him. In the rhetorical battlefield, often the one with fewest principles has the greatest leverage. An enlightened troll, thick-faced and black-hearted, is cynical enough to build any truth that’s convenient.

Many rogue states push for new human rights in international courts, and it isn’t because they were doing a stellar job with the old ones and are looking for new challenges. The goal there may be values-inflation and false-equivalence between the “classic” human rights violations of the dictatorship and the new, stranger rights that might find democratic nations in violation. The weapon is turned against its user.

Putin made a big speech on Crimea a couple of weeks ago, where he invoked Russian history and Western precedents that he wanted his actions compared to. Leaving aside whether the comparisons were apt, do you believe that Putin’s government’s decision-making took these Western precedents into account? Does he have a history of working within this broad, international legal framework that he presented that day? I don’t think it’s that controversial to say no, this was a cynical use of rhetoric.

The hate group that wishes to restrict someone else’s free speech happily hides behind it when convenient. Every aggressor in the modern world is waging a defensive war, obviously. The list goes on.

II. The Partisan Mind

via Slate:

Yale law school professor Dan Kahan’s new research paper is called “Motivated Numeracy and Enlightened Self-Government,” but for me a better title is the headline on science writer Chris Mooney’s piece about it in Grist: “Science Confirms: Politics Wrecks Your Ability to Do Math.”

Kahan conducted some ingenious experiments about the impact of political passion on people’s ability to think clearly. His conclusion, in Mooney’s words: partisanship “can even undermine our very basic reasoning skills…. [People] who are otherwise very good at math may totally flunk a problem that they would otherwise probably be able to solve, simply because giving the right answer goes against their political beliefs.”

III.

Explaining away cultures, from the community of Ta-Nehisi Coates:

Your post sends me back to The North American Review, which asked, in 1912, “Are the Jews an Inferior Race?” It answered the question, resoundingly, in the negative, but the more salient point is that the point was then very much in doubt. After the long centuries Jews spent in Europe marked as a minority, tolerated or persecuted, there was no shortage of thinkers willing to advance the claim that Jewish inferiority was innate, or at the very least, an ineradicable element of a broken culture. “Based on anthropology and biased by personal psychology,” explained the author, “anti-Semitic literature advances the theory that the Jewish race is divested of the higher forms of genius and is to be regarded as an uncreative, imitative, practical, and utilitarian body. Mental inferiority and spiritual impotency circulate accordingly in the very blood of the Jew.”

The article was, itself, a response to a letter in a previous issue that considered that the Jews, in “all their immiscibility,” had survived centuries without sovereignty only at the cost of producing, “a character so unattractive, even repellent, their shortcomings even in righteousness and their insignificance in everything else, without poetry, without science, without art, and without character.”

That’s one example. There are innumerable others. My point is that, at the time, it seemed perfectly reasonable to conclude that Jewish culture, whether innate or the product of prolonged persecution, had itself become a significant impediment to success. But that, a century later, it seems impossible to reconcile the idea that Jewish culture was the problem with the record of success that Jews produced over the following hundred years, in those nations in which they were not similarly persecuted.

Now, we get Jed Rubenfeld explaining how that same culture—formerly blamed for Jewish inferiority—is actually a distinct advantage. And just so, a hundred years from now, there will be bestsellers explaining how black culture, forged in centuries of adversity, accounts for the remarkable success of the African-American community. The point is that the same sets of cultural characteristics operate very differently in different circumstances. And to focus on the culture—rather than the circumstances—seems obtuse.